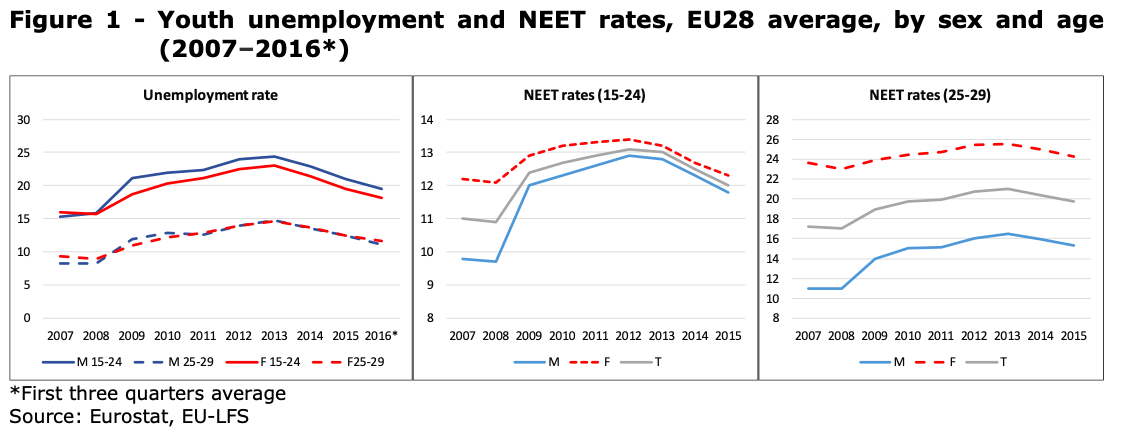

There are gender gaps in the youth employment rates across Europe. The gender gaps are especially significant for youth NEETs rates in age cohort 25-29. It seems young women in almost all European countries are more vulnerable to job losses and they tend to face worse employment conditions than men. Young women are more likely to hold part-time and/or temporary jobs and to earn lower wages than young men. Though almost no gaps are seen among people 15-24, they grow drastically among NEETS in their late 20s. (Young Women’s unemployment in EU).

Why?

‘The analysis shows that gender gaps in the labour market are decreasing between 2007 and 2016, although they remain high among the 25–29 age group; young women are more likely than young men to be NEET-inactive and, when employed, to hold part-time or temporary low-paid jobs, even when they have a high educational level. This might be due to their greater care responsibilities than young men, gender segregation in education and training patterns leading to skill mismatches, difficult access to information channels and job search mechanisms, and labour market discrimination. The different conditions faced by young men and women might also imply that there are gender differences in the effects of employment, education and work-life reconciliation policies which need to be addressed in order to design effective policy measures.’ (Young Women’s unemployment in EU).

What can be done for young women?

Apart from deep societal and cultural changes needed for overcoming uncoscious biases and stereotypes which maintain women in the disadvantaged position, there are a few measures and policy changes that can support young women – especially in role of mother – to balance their work and their private life:

- income-related childcare allowance

- favouring young fathers to leave their work for some periods

- provision of childcare facilities

- support for flexible leave and flexible working measures

- family audits and awareness-raising measures in companies/organisations

It’s crucial ,to keep on reducing fiscal disincentives for lower-earning partners (mainly women) to entering the labour market and promoting policies supporting the work-life balance. In particular, improvements in public childcare provision (number, high quality and affordable services), to offer a real alternative to parental care as well as improvements in accessing to flexible working. This policy mix could be very important to reduce youth gender gaps and to improve the labour market conditions for young women. Policies supporting women’s access to education and training or favouring employability and labour market reinsertion are particularly important in achieving a full participation of young women in the labour market.’ (Young Women’s unemployment in EU).